A few years ago, an article in the Harvard Business Review caught my eye with the analysis that only 8% of leaders excelled at both strategy and the execution of the strategy. This strategy-execution gap was bothersome to me, and seemed to explain at least in part why up to 90% of organizations fail to execute their strategies. And I believe it provides valuable insight into how life sciences commercialization and product launch organizations need to evolve to reach higher commercial performance.

Stages of Strategy-Execution Formalization

As a firm with deep roots in strategic planning and product launch, CREO has the good fortune of serving a diverse portfolio of companies in differing stages of organizational development. At the start of our engagements, we often find clients in one of the following three states of strategy formalization:

- Under-developed Strategy. Fast-moving organizations often have gaps in strategic planning. Leaders often have their hands full trying to manage the day-to-day growth of the business, so time that might otherwise be available for strategic planning can easily get displaced by tactical execution demands. Leaders often experience ambiguity around evolving market conditions, competing organizational priorities, and operational barriers because they have not had the opportunity to align, synthesize, and focus as a team.

- Discrete Strategy Process. For some organizations, strategy is a project that is completed every few years. Though operational concerns may be introduced as inputs into the strategic planning process, the execution of the planning process itself is relatively disconnected from operational considerations. Oftentimes, a greater emphasis is placed on market research and competitive analysis than strategy feasibility or operational alignment.

- Strategy / Execution Handoff. Many organizations recognize the relationship between strategy and execution but treat the relationship as a handoff between phases of work. Under this approach, strategy is still operating as a discrete phase of work, but there is a planned transition from planning to execution. Strategy may be developed on a more frequent basis – perhaps every 12-24 months – and leaders are expected to then develop operational plans that align to the strategy.

Limitations of Current Strategy-Execution Approaches

Though all the above states are understandable, they also pose significant risks to organizations that are trying to grow and launch products. A few of the most common shortcomings our clients report include:

- Strategies don’t get executed. The “strategy” for many organizations is a document that sits on a shelf because there was no mechanism for driving implementation of the strategy in day-to-day operations of the organization.

- Diluted focus. Effective strategies amplify the fewest, most important things that drive goal attainment, and establish the rationale for saying “no” to opportunities that otherwise appear attractive. When strategy and execution are not in sync, leaders and teams with the best intentions tend to naturally drift towards tactics and investments that are good but not necessarily critical to the strategy and its execution.

- Delayed responsiveness to changing conditions. When strategic planning and execution considerations are not synchronized, organizations are less agile and able to respond to emerging issues. Adaptability and responsiveness are critical to effective pivots, especially in life sciences markets where product R&D findings, regulatory approvals, market access, and pricing considerations are continuously evolving.

- Suboptimal implementation. For leaders and teams to execute a strategy properly, they need to understand and embrace it. When strategies are under-developed or built in relative isolation, people critical to realizing the strategy’s vision may not understand what they need to be doing and why to make the vision a reality.

- Lost learnings. No strategy is perfect, and no organization pursues a strategy without encountering both “known unknowns” and “unknown unknowns.” Effective learning is critical to improving both strategies and organizational performance over time, but when organizations lack a timely, disciplined approach to incorporating these learnings, they tend to get lost.

A Better Path to Strategy-Execution Alignment

For these reasons, CREO believes that all three states above do not serve the modern life sciences enterprise well. The days of thinking about strategy and execution as separate and distinct silos should be over. Strategy and execution must be intertwined, driving a virtuous and iterative cycle of planning, performance, and improvement.

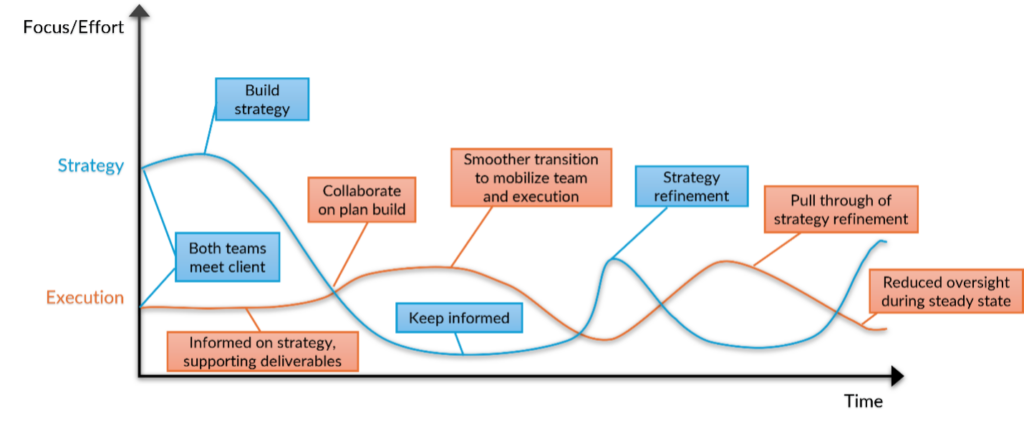

CREO developed a strategic planning methodology called ISEP which is used for corporate strategies and embodies this concept of integrated strategy and execution. This concept of strategy-execution integration is equally applicable to commercialization and product launch teams as well. As the chart below shows, periods of elevated activity specific to both strategy and execution exist just as they naturally do as organizations grow. But under this model, strategy and execution functions collaborate and align on a more continuous basis. The amount of effort – which corresponds to the degree of resource utilization associated with that period of time – fluctuates according to the current needs. And specific cross-over points highlight intentional alignment activities where teams ensure strategies are tuned and execution plans are aligned.

We believe this operating model has several distinct benefits for most product launch and commercial teams in life sciences:

- Stronger alignment on execution. Because neither team “leaves the field,” they remain more intimately connected, focused, and in sync on how to reach their shared commercial goals.

- Improved responsiveness. Teams do not need to wait to incorporate learnings and alter tactics, as they are operating in a more context-aware, real-time environment.

- Lower cost. Though both teams are always engaged, their utilization is dialed up or down in ways that avoid the higher costs associated with a) paying 100% of people costs for resources that are not 100% utilized, or b) paying to re-onboard, educate, and ramp up new resources that change due to lack of utilization.

What do you think – does this approach offer a better path for life sciences commercial teams? I’d love to hear your thoughts.